@Lesnums) Posted on 17/01/14 at 12:17 Share:

@Lesnums) Posted on 17/01/14 at 12:17 Share:

It's winter. You know this, because it's been about two months since the sun decided that it was no longer necessary to rise. It's handicapping, because you would like to take pictures outside a minimum range between 12:34 p.m. and 12:47 p.m., when it is what could be called "daytime". Because there you go, night shots are fine for five minutes, but after a while, the very mention of a night shot gives you hives.

Fortunately, during this period of relative photographic hibernation, it is quite possible to experiment with unknown and fascinating horizons, especially indoors. Let's take a random example (no indeed you're right, it's not random): artistic bokeh. If the technical term means nothing to you, the photographic result on the other hand certainly caught your eye one day.

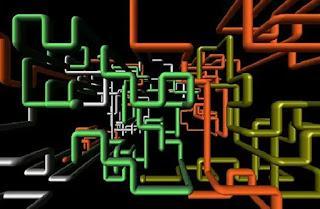

Immediately, it is more telling.

Now that you and I are talking about the same thing, it's time to think about how to spice up this photo exercise. The round, let's face it, is seen and reviewed. So some adventurous photographers had the idea of creating bokeh with very specific shapes to compose their shots. This effect, which may seem complex at first glance, is in fact very simple to achieve, but requires a few essential elements.

To get started, you will need a wide aperture lens. Why ? Because a wide aperture lens has a very shallow depth of field; your background (in which the lights will be) will be all the more blurry. But that's what we're looking for. Ideally, the artistic bokeh starts giving interesting renderings from f/2,8. If your lens opens more, it's all the better. Also, if your lens has a large aperture, you can shoot in low light and that's even better.

Then you will need black cardboard, scissors, tape, possibly a compass, and motivation. The last ingredient is crucial.

Good. Now that all your tools are in front of you, you are going to cut out a cardboard disk the diameter of your lens. You can use a compass or go very "roots" and draw your circle using your goal as a template. Either way, if all goes well, you get a disc.

And in this disk, you will draw a shape. Heart, star, letter or more sophisticated stencil, let your imagination run wild. A technical tip, however: take into account that for your filter to work best, we usually do not cut out a shape whose diameter exceeds the focal length divided by the aperture. For example, if you have a 40mm open to 2,8, your last should be a maximum diameter of 40/2,8 = 14,3mm.

Scotch tape is not a requirement if your stencil fits perfectly within the width of your lens.

Once your stencil is done, you are almost at the goal. Now you just need to attach it to your lens. There are two solutions for this: either your filter fits perfectly and does not move, or it is exactly the diameter of the lens and for some reason is up to you, you do not want to touch it. In this case, four small pieces of tape at the four corners of the filter will settle the matter.

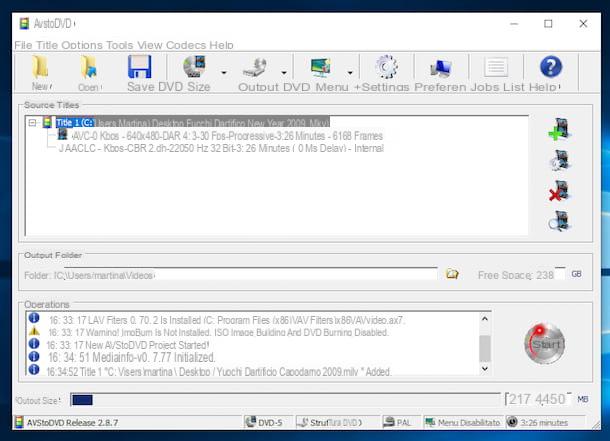

Once mounted, your device should look like this.*

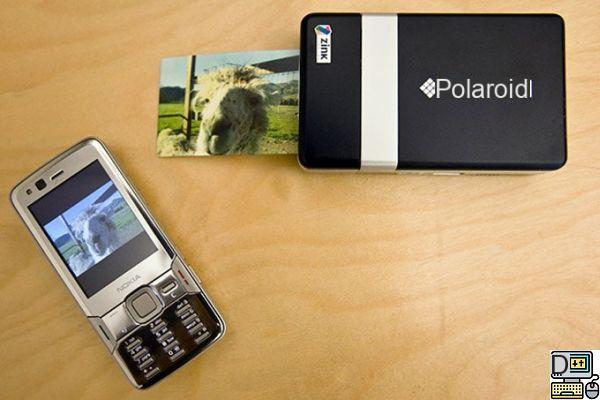

If you have followed these tips to the letter, all you need to do is find a light source to photograph. Above all, do not focus on said source, leave it in the blur, trigger and admire the result.

The fantastic thing about this technique is that you'll get results with outdoor or indoor lighting. There is therefore something for everyone, the chilly as well as explorers of the great cold!

A first try with a stencil in the shape of a "tulip".

Second test with a star-shaped filter.

That said, for those of you who are extremely repulsed by manual work, Photojojo, a more than fantastic site (not because he and I have a common nickname, but because he brings together extraordinary accessories), offers a kit containing 25 bokeh filters, from the most basic to the most elaborate. If after that, you still don't get bokeh, I can't do anything for you.