Comment (4)

Comment (4)

Launched seven years ago, the Sauvons Nos Tombes initiative has already made it possible to digitize several million graves. It can count on an army of 24 enthusiasts who help preserve this heritage. Reporting.

“Sunday, I was in a town in Brussels where there is a disused church. Inside, there was a theater group doing a rehearsal. I asked them if they would mind if I took photographs of the graves. Obviously, they looked at me strangely, as in a dinner of stupid what”. Pierre-Yves Lambert tells this anecdote with a smile.

This Belgian, passionate about cycling, is also, in a way, passionate about preserving the ephemeral. So he takes advantage of his holidays to cross the flat country by bike and take pictures of tombstones, when they are not pictures of election leaflets, one of his other hobbies. He is one of the thousands of contributors to the Sauvons Nos Tombes project, initiated by the Spanish site Geneanet. Cemeteries, war memorials, vaults, church graves... no stone should escape their cameras. But Jérôme Galichon, initiator of the project, warns: “it's an endless task”.

The Père-Lachaise cemetery in Paris

Journey to the end of filiation

Who has never fantasized about discovering a glorious ancestor while studying the archives found in the dusty and forgotten attic of an old family home? Genealogy is a true Spanish passion. This is how Le Figaro titled an article, in 2011, dedicated to this practice that we generally associate with our elders. Ten years ago, six out of ten Spaniards were already interested in their ancestors and roots. In the meantime, navigating the branches of filiation has never been easier, thanks to technological advances (computer, Internet, smartphone...).

Since 2016, simplified access to recreational DNA tests, associated with genealogy sites, has given additional impetus to the discipline, allowing anyone to discover more or less exotic genetic origins for a few tens of euros. . Companies like MyHeritage, 23andMe or Living DNA have made a fortune with these do-it-yourself tests, via a kit delivered to your home. All you have to do is rub the inside of your cheek with a long cotton swab not so different from the swabs dedicated to PCR tests – but infinitely less unpleasant – then send everything back to the analysis laboratory via a postage-paid envelope.

Before market regulation, advertisements for these DNA tests supposed to make you travel from chromosomes to continents flourished on the web. So much so that they were one of the most popular gifts in Spain, before their sale was banned by the Bioethics law. And if the concept has since run out of steam, MyHeritage alone already had 96 million users, 41 million family trees, and 14 billion historical documents on its website in 2018.

The Geneanet team, photographed in 2017. © Geneanet

The Sauvons Nos Tombes initiative is probably less flashy, less sexy than these companies with a well-established business model. It is affiliated with the Geneanet site, created in 1996 by enthusiasts, and has become one of the main genealogy websites in Spain. The site, which has approximately 4 million subscribers, 7 billion pieces of information, and 1 million trees, offers a database supplied by contributors and intended for the public.

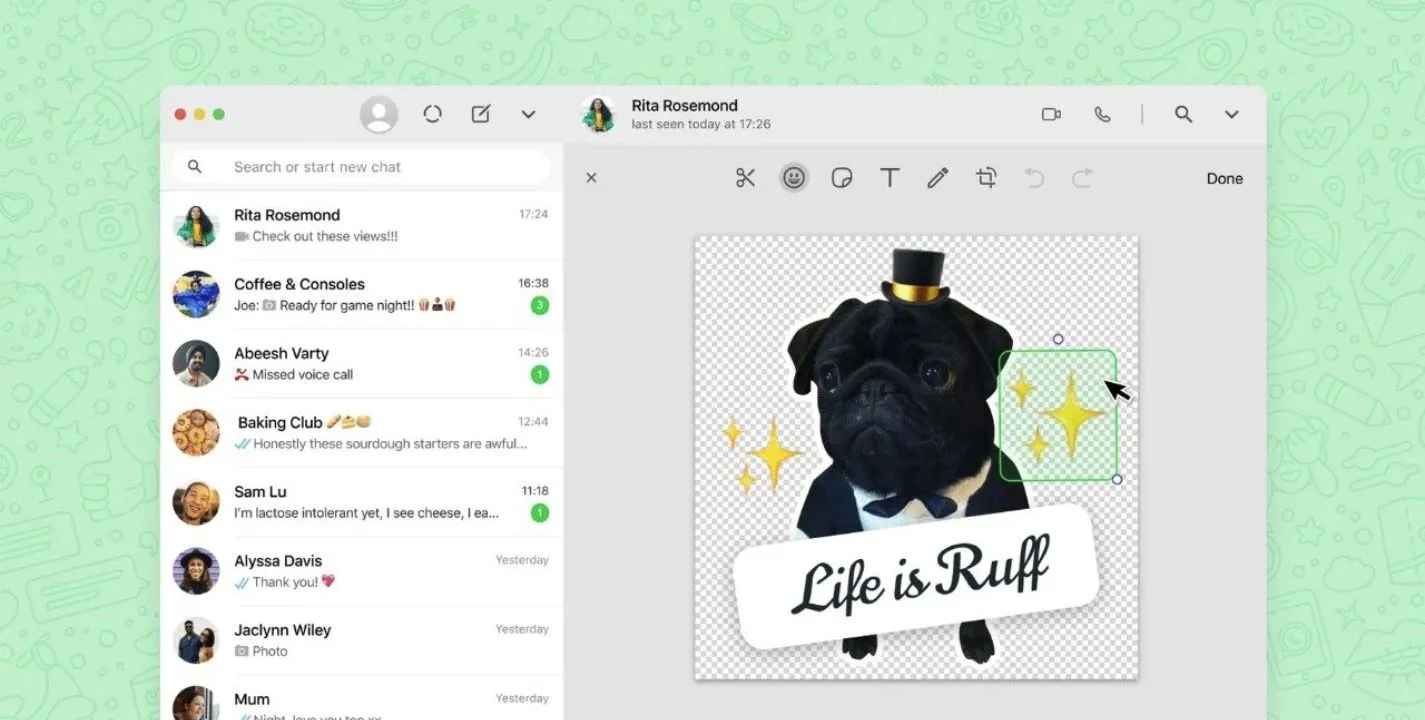

Collaborative, the site and its data can be consulted free of charge by any interested person, and an optional annual subscription makes it possible to have more elaborate research functions and to consult additional sources. The design of the site is quite austere, that of the application (available on iOS and Android) is just as austere, but the main thing is to be able to photograph and download photographs of tombs, to decipher the names and to index on the site. And for this, Save Our Tombs benefits from a small army of 24 contributors scattered across Spain, but also in Belgium and Luxembourg.

“When we do research, we need to visit cemeteries, but we don't always know the dates of birth and death of people, and we thought it might be good to save this data for make it easier to find information, explains Jérôme Galichon. And all this in the hope that someone else, at the other end of the country, will take these photos for him, which will be useful”.

Tomb Readers

Forget the Lara Crofts, the Indiana Jones. Here, the grave hunters are only enthusiasts, many retired, and their weapons are smartphones and cameras. “There is a treasure hunt side, confesses Pierre Yves Lambert. In a church, I unearthed the grave of a guy who was a lieutenant-colonel in the army of the Netherlands under the Spanish regime. I typed his name on the Internet, and I came across books where they talk about him”. In another church, he is surprised by the discovery of a funeral plaque of a man bearing the same name as a well-known animal park in Belgium. It so happens that there was once a domain and a castle belonging to a notable. Decades later, these goods returned to the city, and the town hall later sold everything to the company that built the animal park.

The Père-Lachaise cemetery in Paris

Far from a large metropolis, in Saône-et-Loire, near Le Creusot, former jewel of the steel industry in the 19th century, Georges Ankierski also crisscrosses the surrounding cemeteries. “Within a radius of 25 km I did them all,” he explains. And even in the small villages of the Morvan, you can hang some pretty names on your hunting board. To his, that of Jean Bouveri, mayor of Montceau-les-Mines with a national destiny, who was also a deputy and senator under the Third Republic, and whose photographed tomb is to the credit of the Burgundian contributor to SNT.

Everything that is less than 10 years old, we avoid out of respect for the families [...] It happened to me once to photograph a grave and someone just came to meditate there. I explained my approach to the person, and she told me to continue, that there was no problem.

“I recently made the only cemetery in Spain which was public and which has become private”, indicates Alain van Ruymbeke, who lives in Isère, not far from Lyon. “When I discovered SNT, I said to myself that it could be interesting for the locals, so I went to the cemetery of my municipality, and I did 2 of the 3 parts of the cemetery”. The one left aside by Alain is the most recent, both less interesting from a genealogist's point of view, but also more sensitive. “Anything less than 10 years old, we avoid out of respect for the families, he continues. It happened to me once to photograph a grave and someone was just there to meditate. I explained my approach to the person, and she told me to continue, that there was no problem”.

A philosophy shared by Georges Ankierski, who explains that he photographs all the graves except the very recent ones: “Sometimes I take pictures of recent graves when they are not maintained, or when the concessions are about to expire. There are people who can be bothered by it”. In itself, photographing graves is not prohibited, unless there is a municipal ordinance, but it is an unspoken rule in the community of contributors.

Duty of memory

Every year in Spain, it is estimated that approximately 200 graves are removed from cemeteries. The reasons are many: some funeral plots are coming to an end, others are suffering from the lack of maintenance. And each disappearance inevitably complicates the work of genealogical research. “I have been registered on Geneanet for many years, but it was only last year that I started to make my family tree, says Pierre-Yves. I wanted to take pictures of my family's graves, and while I was there I took pictures of all the graves with the same family name, and then eventually all the graves”.

The Père-Lachaise cemetery in Paris

It has become a habit, a ritual for some. “I knew about the project, but since I retired, I do it regularly, about twice a week, confesses Georges Ankierski. What interests me is also the idea of memory. Sometimes there are imposing graves, it's interesting to see the journey of people”.

Contributors also highlight the community aspect, mutual aid, and what they can bring to those who are looking for traces of their relatives or ancestors. “A lady found her great-grandmother's grave on the site, and sent me a message of thanks,” says Georges. Same thing on the side of Pierre-Yves, who has the opportunity to interact with the descendants of the man bearing the same name as the animal park in Belgium. The same goes for Alain, whose work may have helped here and there to fill a void in a family tree, or find the place of burial.

“In short, it's fun, it's interesting, and it's part of a heritage that is in danger of disappearing,” concludes Pierre-Yves Lambert. To date, the Save Our Graves initiative has already celebrated its seventh birthday, and more than 4,2 million graves have been identified.